IS OUR WATER SAFE TO DRINK?

by J. Gordon Millichap, MD, Pediatric Neurologist, Northwestern University Medical School and the Attention Deficit Disorder Clinic, Division of Neurology, Children’s Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois,

and Kathleen Haviland, JD, Managed Care Specialist, On Lok, Inc., San Francisco, California, and former aide to United States Congressman John D. Dingell.

Material for this article was adapted from Dr. Millichap’s new book, IS OUR WATER SAFE TO DRINK? A guide to Drinking Water Hazards and Health Risks, (ISBN 0-9629115-5-0, PNB Publishers, P.O. Box 11391, Chicago, Illinois 60611)

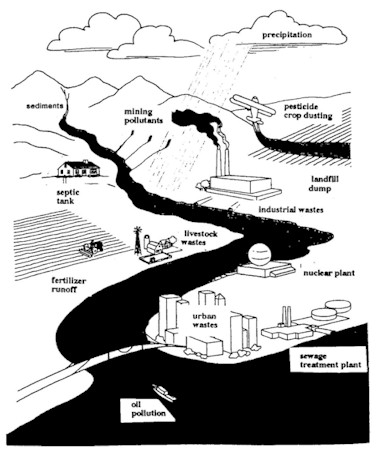

The safety of our drinking water is often taken for granted. In recent years, however, environmentalists and the media have drawn attention to the dangers of ground water pollution and the health risks from lead, chlorine, pesticides, organic chemicals, and various microorganisms that have been found to contaminate our public water supplies. Outbreaks of waterborne diseases are a common occurrence and have involved entire city populations, sometimes leading to serious complications and even fatalities. The potential carcinogenic effects of long-term exposure to certain organic chemicals in our water supplies are of increasing concern in this industrialized society.

What is the United States Government doing to safeguard our water?

The controlling law governing our drinking water is the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) of 1974, as amended. The SDWA provides the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to safeguard public drinking water through regulatory programs that protect groundwater aquifers and to establish standards for the purification, treatment, and testing of municipal water supplies.

Both the House of Representatives and the Senate passed their own versions of the reauthorization of the SDWA in the 103rd Congress, but they adjourned before differences could be reconciled and a law passed. In the new 104th Congress, as of press time, contentious issues are delaying debate over the reauthorization of the Act. The Chairman of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, John Chafee (R-R.I.) is favoring the reauthorization vehicle that he co-sponsored in the 103rd Congress, S.2019, which passed the Senate in May of 1994. S.2019 would have given the EPA greater flexibility to consider the relationship between costs and health benefits when setting future drinking water standards.

However, the Chairman of the Subcommittee on Drinking Water, Fisheries, and Wildlife, Richard Kempthorne (R-ID), is in conflict with his full committee chairman in that he supports much weaker regulatory language. He favors language that would base standards on what is technologically achievable, as opposed to feasible; he also favors language that would require proposed standards to be subjected to explicit cost-benefit analyses and to be justifiable in terms of the risk reduction produced. The proposals in Congress favor a weakening of Federal standards and controls and the transfer of some responsibility for water quality from the EPA to the States and local governments, which are often ill equipped and under funded.

The carcinogenic properties of organic chemicals as well as radionuclides are a main cause for concern. Public health authorities have in the past relied more on filtration and disinfection treatment processes rather than water monitoring to ensure the safety of drinking water, because of the complexity of laboratory analyses. In recent years, more communities are using treatment processes other than disinfection to remove inorganic and organic contaminants. The cost of meeting stricter water quality standards is particularly high for smaller communities.

The proposals in Congress favor a weakening of Federal standards and controls and the transfer of some responsibility for water quality from the EPA to the States and local governments, which are often ill equipped and under funded.

In the State of Illinois, beginning January 1993, all municipal suppliers are required to monitor for 29 synthetic organic chemicals (SOCs), mostly pesticides. All surface water suppliers must test quarterly until no SOCs are detected or the level of each contaminant is below its maximum contaminant level (MCL). Ground water suppliers will test for most of the SOCs before December 31, 1995 unless the present Congress votes to change these regulations and a less restrictive bill is passed into law.

Do we need to spend more on improved water purification technologies and a tightening of EPA standards for potential cancer-causing chemicals, or should we cut costs and limit regulation of contaminants to those known to cause the greatest immediate health risks, for instance, lead? The former solution would result in criticism by state and local governments who find the present regulations to be costly and sometimes impractical, particularly for smaller municipalities, while the latter would probably lead to an even greater incidence of cancer (and other diseases) among our citizens and will certainly cause an outcry from environmentalists who are pressing for more stringent controls.

Is the consumer sufficiently informed of risks?

There is a need for education of consumers regarding the sources and types of water contamination, the recognition of symptoms of waterborne diseases, and home methods for prevention and control of drinking water hazards. Some waterborne health hazards, such as lead, nitrate, arsenic, and mercury, can be avoided by having municipal or well water checked and by taking certain precautions. For example, to avoid lead from old plumbing, flush the faucet until the water is cold before drinking.

Bacterial contamination should be suspected at times of flooding or earthquake. The water should be boiled or chlorinated, or bottled water substituted. A sudden change in water appearance from clear to turbid might suggest contamination with the parasite, Cryptosporidium, the organism that caused serious diarrheal illness in one half million of the population of the city of Milwaukee in the spring of 1993, with 100 fatalities. Avoidance of water that loses its clarity or develops an unpleasant odor or taste could protect the consumer from potential health risks caused by a faulty public water filtration system.

There is a need for education of consumers regarding the sources and types of water contamination, the recognition of symptoms of waterborne diseases, and home methods for prevention and control of drinking water hazards.

While these simple consumer tips and precautions may help in avoidance of acute illness caused by waterborne microorganisms and certain inorganic pollutants, for example, nitrate and arsenic, the far more serious danger of the chronic and lifetime exposure to potentially carcinogenic organic chemicals will persist and remain unanswered. Only our government and a more environmentally responsible corporate industrial society can lower the carcinogenic hazards lurking in our water and food supplies, since only they have the resources to prevent or remove these contaminants.

Is the medical profession sufficiently aware of the problem?

The massive outbreak of Cryptosporidium parasitic infection in Milwaukee in 1993 was a reflection not only of the inadequate filtration system and inefficient water quality monitoring but also resulted from the slow response of physicians to recognize and diagnose the cause of the waterborne illness in patients who sought medical help. Cases were misdiagnosed as viral gastroenteritis or "intestinal flu" without further investigation, and the special testing procedures required for the detection of Cryptosporidium in stools examined for ova and parasites were not requested. The delay in diagnosis resulted in an outbreak involving nearly one half a million individuals. If the medical community had been more alert to possible contamination of water supplies with parasites, the outbreak would have been contained and the deaths of 100 patients may have been prevented.

. . . a federal lawyer for the AMA stated that "clean water is an environmental and political issue and not strictly a health matter." This apparent disinterest or ignorance of the hazards and health risks of contaminated water by representatives of our medical profession is alarming.

In the treatment and prevention of various cancers, the influence of environmental factors, especially chemical and viral contamination of drinking water and foods, has received little attention in medical oncology research. The American Medical Association is not actively involved in lobbying for cleaner water and the passage of legislation to maintain strict governmental controls of water resources. In answer to a question regarding the role of the AMA in the present overhaul of the Clean Water Act, a federal lawyer for the AMA stated that "clean water is an environmental and political issue and not strictly a health matter." This apparent disinterest or ignorance of the hazards and health risks of contaminated water by representatives of our medical profession is alarming.

Contamination of Public Water Supplies and Microbial Disease Outbreaks

The safety and quality of drinking water in the United States are dependent on the efficiency and maintenance of the water treatment processes commonly used in most public water systems. The removal of microorganisms by disinfection and filtration has dramatically reduced the incidence of waterborne diseases such as typhoid fever, cholera, and hepatitis, and the banning of lead in pipes and solder has reduced the exposure of millions of Americans to lead and the risks of lead poisoning.

The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 and the Amendments of 1986 set standards of drinking water quality to protect our health, but deficiencies in filtration technology and regulatory programs enforcing these goads have led to numerous outbreaks of disease. Tests employed to check for certain parasitic organisms and viruses are sometimes inadequate and the disease causing or pathogenic nature of parasites such as Blastocystis hominis, especially in immuno-compromised individuals with cancer or AIDS, is often not recognized.

The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 and the Amendments of 1986 set standards of drinking water quality to protect our health, but deficiencies in filtration technology and regulatory programs enforcing these goads have led to numerous outbreaks of disease.

A total of 96 outbreaks of waterborne disease reported to the Center for Disease Control and the Environmental Protection Agency, 1986-1992, accounted for 46,712 confirmed cases of gastrointestinal illness. The majority of cases were either of unknown cause, presumed viral in origin, or traced to Crybtosporidium. Other common organisms were Salmonella, E. coli, Campylobacter, and hepatitis A. Since the 1993 outbreak in Milwaukee, Cryptosporidium has outnumbered all other organisms in terms of numbers of individuals affected by waterborne illness.

Drinking water suspected of bacterial contamination should either be boiled, chlorinated, or bottled water substituted. Chlorination will not remove Cryptosporidium and the water must be boiled or filtered by reverse osmosis.

Lead in Our Drinking Water

Lead in drinking water contributes between 10 and 20 percent of the total environmental exposure to lead. Young children are particularly susceptible to lead poisoning, and even low dose exposure can cause intellectual deficits and behavior disorders. Water as a source of lead poisoning may increase in relative importance since leaded gas has been abolished and abatement programs have reduced exposure from lead-based paint and urban soil and dust.

Chlorination will not remove Cryptosporidium

The EPA estimated in 1986 that some 40 million Americans were drinking water that contained potentially hazardous levels of lead. Until 1993 the EPA limit for lead levels in drinking water was 50 parts per billion (ppb). The new limit for lead has now been set at 15 ppb. Approximately half a million children with hazardous lead levels in their blood will be benefited, and lead exposure will be minimized for millions of Americans.

Simple consumer steps to reduce lead exposure from drinking water

These include the following:

|

|

Contaminants Peculiar to Well Water

Coliform bacteria, nitrates, and arsenic contaminate well water more commonly than municipal water supplies. The presence of nitrates suggests that animal or human wastes or fertilizers used in agriculture or on lawns are entering the well from land runoff, seepage, or migration into ground water aquifers. Nitrates are of special concern to the health of young children, and in women of child-bearing age. Nitrates converted to nitrites in the stomach cause methemoglobinemia in infants. The hemoglobin in the blood is oxidized to methemoglobin, a form of hemoglobin that cannot bind and carry oxygen from the lungs to the tissues. The blood turns a chocolate brown color and the patient’s skin becomes gray blue or cyanotic. Water containing nitrate in amounts greater than the permitted maximum contaminant level (MCL, 10 mg/L) should be avoided and bottled water substituted. Nitrate-containing water should not be boiled, since evaporation will result in increased concentrations of nitrate.

Nitrates are of special concern to the health of young children, and in women of child-bearing age.

An outbreak of methemoglobinemia in New Jersey in 1992 involved more than 40 elementary school children in first through fourth grades. They visited the school nurse within a 45-minute interval following the school lunch period. They all suffered from an acute onset of blue lips and hands, vomiting, and headache. Fourteen were hospitalized, and all recovered in 36 hours. The outbreak, due to nitrite poisoning, was traced to soup contaminated by nitrites in a boiler additive. The authors of this reported incident aptly named the soup "Boilerbaisse."

Nitrites are also potentially carcinogenic. They act on amines in the diet to form nitrosamines, which have been shown to cause cancer in animals. High levels of nitrate have been found in well waters of regions of China, Columbia, and in two towns in England where the incidence of stomach cancer is unusually high. A link between nitrate in well water and cancer of the stomach needs further investigation.

EPA National Survey of well water

The EPA has completed a five-year national survey of nitrate and pesticides (NPS) in drinking water wells. Of 10 million rural domestic wells that were studied, nitrate was detected in 57 percent, pesticides in 4 percent, and both in 3 percent. The pesticides detected most frequently in the survey were DCPA (Dacthal) acid metabolites and atrazine. DCPA is a herbicide used primarily as a weedkiller on lawns, turf, and golf courses, and on some fruits and vegetables. Atrazine is used to control annual broadleaf weeds and grasses in corn and soybean farms.

Pesticides had been used at about 80 percent of homes and farm properties where domestic wells were located. These pesticides migrate through soil and some had concentrated in rural domestic wells at levels above their maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) and health advisory levels (HALs).

Pesticides had been used at about 80 percent of homes and farm properties where domestic wells were located. These pesticides migrate through soil and some had concentrated in rural domestic wells at levels above their maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) and health advisory levels (HALs).

A variety of potentially carcinogenic chemicals used in industry, business, or households may endanger the safety of drinking water obtained from wells. The evidence of widespread migration of chemicals into wells demonstrates the need for improved ground water protection.

Well owner safety tips include the following:

|

|

Cancer Related Water Pollutants

Cancer related hazards in drinking water are man-made and are derived from industrial, domestic, and agricultural wastes, the polluted atmosphere, leaching from soil, land runoff, motorboat engines, and spilled chemicals. There are four main groups of potential carcinogenic chemicals:

1) synthetic organic chemicals (SOCs)—pesticides including lindane, chlordane, 2,4-D, endrin, and toxaphene;

2)volatile organic chemicals (VOCs)—industrial chemicals and solvents, degreasing agents, varnishes, and paint thinners, including carbon tetrachloride, vinyl chloride, and benzene;

3) polychlorinated biphenyls PCBs)—waste products from electrical transformer, capacitor, and plasticizer factories, banned in the 1970s but persisting in the water of rivers and the Great Lakes, where they were dumped years ago; and

4) trihalomethanes (THMs)—by-products of chlorine disinfection of drinking water, especially chloroform.

The disinfection of water with chlorine is the source of cancer risk receiving most attention from the EPA. The Food and Drug Administration in 1976 restricted the use of chloroform that previously had been employed in cough syrups, mouthwashes, toothpastes, and other common consumer products. The cancer risk of exposure to chloroform may have decreased over the past 20 years, but chloroform in drinking water is a significant cancer-related hazard.

The disinfection of water with chlorine is the source of cancer risk receiving most attention from the EPA.

The EPA regulates and monitors the maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) of organic pollutants, and the World Health Organization (WHO) issues guideline values, the concentration of a chemical in drinking water associated with an estimated risk of one additional case of cancer per 100,000 population over a lifetime of 70 years exposure. None of these guidelines take into account the additive and synergistic effects of the vast number of chemicals to which we are exposed.

Cancer Risk: Incidence and Assessment

Cancer may be caused by a combination of factors, both environmental toxins and internal susceptibility. Environmental causes include chemicals, infection with viruses, and ionizing radiation. Internal factors are hormonal, changes in the immune system, and inherited mutations. An interval of ten or more years may pass between exposure to chemicals or radiation and the clinical signs of cancer. A steady rise in cancer mortality rate in the United States has been recorded by American Cancer Society statistics in the last 50 years. One out of every five deaths is from cancer and more than one half million deaths from cancer are expected this year.

Although lung cancer is the major reason for this increased incidence, other forms of cancer are also responsible for the increased cancer mortality. For example, breast cancer incidence rates for women have increased about 2 percent a year since 1980, and they now number 110 per 100,000. Breast cancer is the second major cause of cancer death in women and, unlike many other cancers, a five year survival does not necessarily mean a cure of breast cancer. The number of deaths from breast cancer per 200,000 population in 1961 was 24,311 and in 1991, it had risen to 43,583, an increase explained partly by the aging of the population but also by a greater profusion of industrial and agricultural organic chemicals in our environment.

Risk assessments are therefore very rough estimates.

The determination of potential cancer risk from chemicals in water and food is usually based on long-term animal studies. Data are also available on the incidence of cancer in humans, mostly from occupational exposure. Risk assessment is in two stages: 1) identification of the toxic properties of potential carcinogens, and 2) measurement of the degree of human exposure to the chemical.

Chemical hazards are tested for oncogenicity in laboratory animals or cell systems and in clinical and epidemiological studies. Levels of exposure through air, water, and food are measured and the degree of contact with the hazard is estimated. Risk assessment is usually based on high-dose exposure for a short time in animals. In setting human safety standards, scientists must extrapolate from animals to humans and from high-dose acute exposures to low-dose long-term conditions. Risk assessments are therefore very rough estimates. The EPA tends to rely on data showing the highest incidence of cancer for setting regulatory controls, but some authorities question the value of present estimates from laboratory animals and call for improved methods more relevant to humans.

Water source and risk

Epidemiological studies of populations exposed to surface, upland, chlorinated, and reused waters have demonstrated an increased incidence of cancer of the gastrointestinal and urinary tracts. As one example of a population-based approach, United States case-controlled studies in New York counties compared mortality from gastrointestinal and urinary tract cancer with noncancer death controls. There was an excess of male deaths in chlorinated surface water areas from cancer of the esophagus, stomach, large intestine, rectum, liver, kidney, pancreas, and bladder, and an excess of female deaths from cancer of the stomach.

Upland surface water and polluted river sources that have been chlorinated carry the highest risk of cancer. Unchlorinated ground water has the lowest cancer risk.

In England, the relative risks of river Thames reused water and upland water compared to ground water showed a statistically significant increased risk of stomach cancer mortality in persons supplied by upland and river water for drinking purposes.

Upland surface water and polluted river sources that have been chlorinated carry the highest risk of cancer. Unchlorinated ground water has the lowest cancer risk. Studies have shown sufficient evidence of a cancer risk associated with organic micropollutants in certain drinking waters that a causal relationship has been accepted. The high prevalence of polluted and chlorinated waters in public supplies demand the enforcement of EPA regulations to monitor the MCLs of organic pollutants.

Consumer risk assessment factor

Consumers vary in the way they view these hazards and their respective risks. Some will accept a small risk without concern for health effects whereas others will view any risk as unacceptable and cause for alarm.

"Is the Water Safe to Drink?" not "How Safe is Our Drinking Water?" is the question asked by many consumers at a personal level. Unfortunately, a simple "yes" or "no" answer is not possible, given the many variables in water sources, environmental factors, and water treatment processes. Clearly, there is a risk involved by ingesting low levels of organic chemical contaminants every day of our lives. That one additional case of cancer per 100,000 population might be someone close!

The following guidelines relate to possible carcinogens in our drinking water:

|

|

Bottled Water Usage and Safeguards

Public concern with both the quality and safety of drinking water has become so compelling that many consumers now rely almost exclusively on bottled water for drinking purposes. Bottled water is now preferred by millions of Americans and the cost is enormous. To learn that regulations governing the purity and safety of bottled water are often less stringent than those for municipal water supplies may come as a surprise to some consumers.

Bottled water is a luxury to many and a necessity to others. Company advertising has promoted bottled water as "purer," "safer,<!70> "chlorine-free," and an essential component of a healthy lifestyle. It is not generally recognized that one-third of all bottled water in the United States comes from public water supplies and is no safer than the water obtained from the faucet.

An Environmental Policy Institute Report (1989) refers to the frequency of contamination of bottled water with low levels of heavy metals, solvents, and bacteria. The carcinogenic chemical migrants (for example, methylene chloride and vinyl chloride) from plastic bottle containers are also a concern. Despite the value of bottled water as an alternative source of drinking water at times of emergency, consumers should not presume that bottled water is invariably preferable to tap water.

Buy bottled water

|

|

Consumer Concerns and Home Water Treatments

The most frequent questions asked by consumers are about the level of lead in their drinking water and about taste and odor problems. "Is our water safe to drink?" "Do we need to substitute bottled water?" "Should we install a home water treatment unit and, if so, which type of unit would be most satisfactory for our particular needs?"

The EPA provides information in response to inquiries about the necessity for home treatment units. It does not regulate the manufacture, distribution, or use of these units. The EPA stresses that the units should not be relied upon for the removal of organisms and chemicals injurious to our health. Nonetheless, certain filtration units, especially reverse osmosis, will lower the concentration of several contaminants, including lead, copper, nitrates, pesticides, and parasites. No system is warranted for complete elimination of all contaminants.

The government and the medical profession appear to be failing in their duties.

Controversies concerning the sale and use of home treatment units have arisen because of unsubstantiated claims of benefits and scare tactics. Consumers should beware of "free" water testing by a salesperson to determine the drinking water quality. An independent analysis is usually more accurate and meaningful.

Conclusion

The government and the medical profession appear to be failing in their duties. The former should ensure the safety of our drinking water and the latter should recognize of health risks associated with contaminants. The more we understand about our own local water supplies and the nature of the health risks, the more we as consumers and citizens can do to protect ourselves from these hazardous environmental pollutants and their sources.

_____________

Selected Bibliography

American Academy of Pediatrics, 1994 Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 23rd edition, Elk Grove Village, Illinois.

Askew, G.L. et al., "Boilerbaisse: an outbreak of methemoglobinemia in New Jersey in 1992," Pediatrics 94:381-4, September 1994.

Baghurst, P.A., et al, "Environmental exposure to lead and children’s intelligence at the age of seven years," New England Journal of Medicine 327:1279-84, October 29, 1992.

Baron, E.J., L.R. Peterson, S.M. Finegold, Bailey and Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology, 9th edition, Mosby, St. Louis, 1994.

Mackenzie, W.R., N.J. Hoxie, M.E. Proctor et al., <169.A massive outbreak in Milwaukee of Cryptosporidium infection transmitted through the public water supply," New England Journal of Medicine 331:61-7, July 21, 1994.

Millichap, J.G., Environmental Poisons in Our Food, PNB Publishers, Chicago, 1993.

Millichap, J.G., Is Our Water Safe to Drink? A Guide to Drinking Water Hazards and Health Risks, PNB Publishers, Chicago, 1995.

Ram, N.M., E.J. Calabrese, R.F. Christman, Organic Carcinogens in Drinking Water: Detection, Treatment, and Risk Assessment, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1986.

U.S. Center for Disease Control and EPA, "Waterborne disease outbreaks, 1986-1992," Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports, 1990, 1991, & 1993.

U.S. Congress House Floor Brief, "Safe Drinking Water Act of 1994," October 7, 1994.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, National Survey of Pesticides in Drinking Water Wells, Phase1 Report, Washington , D.C., Office of Water, Office of Pesticides and Toxic Substances, EPA, November 1990.

Idem., "Home water treatment units: Filtering fact from fiction," EPA, Washington, D. C. 1992.

Idem., "Drinking Water Protection: A general overview of Safe Drinking Water Act Reauthorization," Office of Water, February 1994.

Article from NOHA NEWS, Vol. XX, No. 4, Fall 1995, pages 3-8.