OUR OPTIMAL NUTRITIONAL NEEDS: WHAT ARE THEY AND CAN WE MEET THEM

Humanity is in the midst of a world crisis. We are rendering ourselves toxic and malnourished while simultaneously destroying the ecological balance that supports life on earth. The rate of population growth has far outstripped the rate of ecologically sound production, geometrically complicating an already perilous world state.

The newly released Kellogg report, The Impact of Nutrition, Environment & Life-style on the Health of Americans, by Joseph D. Beasley, MD, and Jerry J. Swift, MA, gives us a comprehensive look at the state of our health in the United States, with the above warning and many recommendations. More than seven years in the making, this report was funded by grants from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and the Ford Foundation, though the authors state that the report reflects their own views and not those of the foundations. Given its length (735 pages), the report is amazingly readable and accessible. Its fundamental emphasis is on optimal nutrition, which its authors, however, consider unobtainable in any absolute sense, as every persons needs change from day to day. Nevertheless, much can be learned from this book; a few highlights follow.

Nutrition

Nutrition involves the use of materials (food, water, and air) that

must be obtained from outside our bodies. These materials are used by

our tissues right down to the cellular and subcellular levels. Throughout

the book, Beasley and Swift emphasize biochemical individuality and the

work of the late Roger J. Williams, PhD, whose 1971 book, Nutrition

Against Disease, inspired the founding of NOHA, and who became an

honorary member of NOHA. (This book, they say, is "probably the best

single book on the relationship of poor diet to illness.") Our organs

and tissues vary from person to person by orders of magnitude. Even more

important are the tremendous variations in our enzymes, those substances

essential for the amazingly rapid millions of chemical reactions that

take place daily in our bodies. Coded for by our genes, these enzymes

also depend on many different essential nutrients that we must obtain

from outside ourselves.

Our organs and tissues vary from person to person by orders of magnitude. Even more important are the tremendous variations in our enzymes, those substances essential for the amazingly rapid millions of chemical reactions that take place daily in our bodies.

How many essential nutrients are there? The report lists the fifty essential nutrients for human beings the nutrients we need in order to stay alive that have been discovered to date. There are very likely more, and some experts debate the inclusion of a few. While strictly speaking this definition would include the oxygen we breathe, it is conventionally limited to essential substances obtained through digestion:

Given the basic materials (the nutrients) they need, the gene/enzyme complexes of human cells can assemble all the chemical compounds that make up the human body and keep it running efficiently. There are over 50,000 of these compounds or millions if one counts all the different antibodies the body tailors to attack invaders. . . . Nutrients vary extremely widely in the amount needed from millionths of a gram to pounds per day.

The five major nutrients, or macronutrients protein, carbohydrate, fat, water, and fiber comprise 99.99 percent of what we eat. Protein, which is formed from amino acids, is "the key constituent of all animal bodies, accounting for 10 percent to 20 percent depending on age and body weight. (Most of the rest is water, fat, and the calcium of bones and teeth.)" Proteins consist of countless combinations of 22 amino acids. With about half of these amino acids our bodies can build the others. Our best source is the animal kingdom. Because plant proteins are usually low in certain amino acids, they need to be carefully combined with foods that supply complementary amino acids. While some Third World nations have diets adequately combining amino acids, as in beans and rice, many such nations "do not enjoy our abundant supplies of meat and dairy foods that is, of complete protein . . . most often the cutting edge of malnutrition is not so much a lack of food as the absence of specific nutrients, such as essential amino acids.

. . . three fatty acids linoleic, alpha-linolenic, and arachidonic are known to be essential for human life. However, they are often refined out of processed foods, since, unrefrigerated, they would turn rancid and reduce shelf life.

A source of energy is essential to life. Usually the carbohydrate foods we eat are our source of energy. Fats, however, can be burned for energy. In fact, over the millennia of our development, fats have been used for energy storage for times of food shortage. In dire circumstances, protein can also be burned for energy. In this sense, carbohydrate is not an essential nutrient just a convenient source of energy. On the other hand, three fatty acids linoleic, alpha-linolenic, and arachidonic are known to be essential for human life. However, they are often refined out of processed foods, since, unrefrigerated, they would turn rancid and reduce shelf life. Fats and oils in whole foods, which do contain these fatty acids, "provide many of the factors needed for their own digestion and metabolism (cholesterol, lecithin, and vitamin E) and supply us with energy, warmth, protection, and essential nutrients. [But] intensive processing denatures natural fats and oils, stripping them of these beneficial factors and introducing known risk factors such as trans-fats and free radicals." Thus the authors recommend that we "eat moderate amounts of natural fats found in fish, olives, nuts, butter, milk, cheese, cold-processed oils, wheat germ, and meats. Avoid margarine and other hydrogenated oils. Cut down on highly processed polyunsaturated oils. Where needed, use butter, olive oil, and a variety of cold pressed oils. Keep these products covered and refrigerated when not in use."

Water is an essential nutrient for all living creatures. "Many organisms can live without air, but none can live without water."

Fiber, though actually a nonfood because we cannot digest it, is paradoxically a "nutrient." Found in the protective walls of plants, in the husks of seeds, and in their mature fruit, fiber is thought to have several important roles in human health and nutrition: Keeping the digestive process moving smoothly, binding potentially harmful substances and keeping them from being absorbed by the body, and modifying certain compounds, such as bile salts, cholesterol, and triglycerides, before absorption.

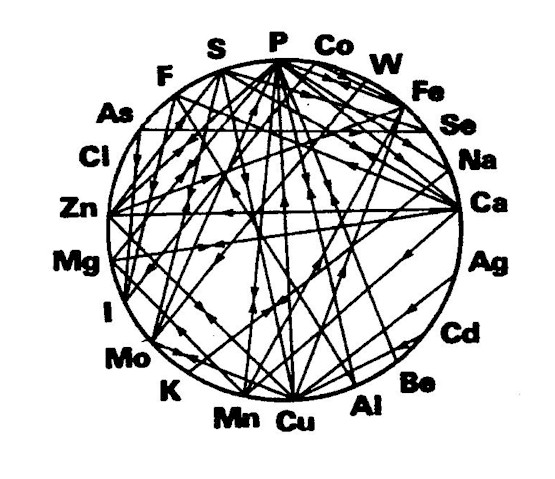

The micronutrients minerals and vitamins, also essential to our life and health are needed in tiny amounts: "In the harmony of nature, they also occur in foods only in minute amounts. (Any more and such essential nutrients as florine and selenium would kill us.)" Biochemical research in addition to discovering more and more essential nutrients, has been uncovering their complicated interrelationships. (see the accompanying chart for some of the known interrelationships among certain elements, not all of which are essential nutrients.)

Nutritional Relationships Between Elements

Each arrow means that the element is needed for the utilization, and/or

too much interferes with the absorption, of the element to which the arrow

points. For example, copper (Cu) is needed for the utilization of iron

(Fe), but too much copper can markedly decrease iron absorption. Paired

arrows indicate reciprocal effects. (Published with permission)

For some time recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) for nutrients have been developed from population studies of average requirements, the original concern being the lethal diseases that can arise from deficiencies. The population is usually assumed to be a bell shaped normal curve, and some allowance is made for variance from the average. Beasley and Swift, however, point out that the median (with half the people above and half below) is a more meaningful measure when we have a skewed population, as often occurs when measuring nutrient absorption. To illustrate the difference between the average and the median, imagine that if we are measuring annual income in an impoverished village of 50 people surrounding the home of a millionaire, we could very well find an average annual income of $100,000, but the median annual income would be only $200! The authors think that when we use the median we are more likely to remember that half the population has a value lower than the one presented. Also, the authors say that based on our knowledge of biochemical individuality, the RDAs are misleading whenever we think of them as applying to ourselves individually. They suggest that the RDAs be renamed minimum population requirements (MPRs) and interpreted accordingly. The central problem in nutrition today, they believe, is "how to determine the optimal nutrient needs of any individual." Fortunately, research culturing an individuals lymphocytes (from his or her blood) in up to 200 different nutrient-combination mediums and observing the response is currently under way. This procedure shows promise of individualizing nutritional assessments.

. . . the authors say that based on our knowledge of biochemical individuality, the [recommended dietary allowances] RDAs are misleading whenever we think of them as applying to ourselves individually. They suggest that the RDAs be renamed minimum population requirements (MPRs) and interpreted accordingly. The central problem in nutrition today, they believe, is "how to determine the optimal nutrient needs of any individual."

The authors point out at length the nutrient losses that occur in the growing, transportation, storage, cooking, and refining of food. In regard to the latter, Jean Mayer, MD, in A Diet for Living (1977), has said that "sugar is a new food. It didnt exist in the West until the seventeenth century. And the argument that sugar is an essential food is a lot of nonsense." According to Henry A. Schroeder, MD, in The Trace Elements and Man (1973), "Refining of raw cane sugar into white sugar removes most (93 percent) of the ash, and with it go the trace elements necessary for the metabolism of the sugar: 93 percent of the chromium, 89 percent of the manganese, 98 percent of the cobalt, 83 percent of the copper, 98 percent of the zinc, and 98 percent of the magnesium. These essential elements are in the residue molasses, which is fed to cattle." We also have the problem that all fiber, which could assist in digestion, is removed from the sugar. Furthermore, say the authors:

Refining is a nutrient-devastating series of industrial procedures. Indeed, the term "refining" is actually a cosmetic word for the process of extracting: the industrially workable material is extracted from foodstuffs and, though stripped of most nutrients, is sold as "refined". . . . The two predominant refined foods in the Western diet, sugar and flour, have a common birth. In the latter nineteenth century, the food industry began applying mechanical technology to the preparation of foods for sale commercially. By their nature, wheat grain and sugar cane lent themselves to this kind of treatment all too well. Both after extensive extracting ended up as fine white powder that went right to the head and heart of the public (rather like heroin or cocaine in some subpopulations today). It was "addiction" at first taste.

"psychiatrists who ignore nutrition and most do may thereby be profiteering off many of their patients, albeit unconsciously. And prescribing tranquilizing drugs only exacerbates the underlying malnourishment."

While the link between diet and heart disease or other chronic physical conditions is widely accepted, it is less well known that nutrition can affect human behavior and personality. Yet pioneering research at MIT has shown that "rapid and specific changes in brain composition normally occur after each meal." Other researchers have found that brain abnormalities associated with learning and behavioral difficulties appear related to "neurotransmitter precursor imbalances, vitamin and mineral deficiencies," and "the consumption of refined carbohydrates, toxic elements, additives, colorings, caffeine, and allergens." These and other observations indicate that what an animal eats "causes characteristic changes in brain composition," implying the starting possibility that brain neurotransmitter levels can be "subject to the vagaries of what one chooses to eat for breakfast." Similarly, behavioral changes "in advance of medical symptoms" from vitamin B2 restriction in human subjects have been reported, and ample evidence of hypochondriasis, depression, and hysteria following deprivation of certain vitamins has been found.

The authors conclude that "psychiatrists who ignore nutrition and most do may thereby be profiteering off many of their patients, albeit unconsciously. And prescribing tranquilizing drugs only exacerbates the underlying malnourishment."

Environment and lifestyle

Modern medicine, according to Beasley and Swift, has been tremendously successful in dealing with infectious diseases and with trauma from sudden accidents. Historically, it was unbelievable that particular diseases could be caused by microorganisms too small to be seen by the naked eye. Great progress was made when bacterial pathogens and antibiotics that would kill them were discovered for many diseases. The paradigm, or overall mindset, of modern medicine has been to diagnose a disease and to find and treat the single cause. This procedure has been wonderfully effective with many infectious diseases and also with overt injuries.

the industrially workable material is extracted from foodstuffs and, though stripped of most nutrients, is sold as "refined". . . . By their nature, wheat grain and sugar cane lent themselves to this kind of treatment all too well. Both after extensive extracting ended up as fine white powder that went right to the head and heart of the public (rather like heroin or cocaine in some subpopulations today). It was "addiction" at first taste.

However, the main diseases that kill and make us ill today in America are the chronic diseases of all our major organs, including the heart, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and brain. These illnesses are multifactorial they do not come from a single cause so that prescribing a single drug or a single nutrient does not address the true situation. We need a new paradigm in medicine a new comprehensive approach to chronic disease. The authors point out by analogy that in physics today we no longer deal with Newtonian cause and effect but rather with relativity theory, and in biology some scientists have shown the advantages of a systems approach in which we deal with a total organism and their feedback mechanisms. We can begin thinking of the whole person all the nutrients needed, the past and present environmental impingements, and the needed lifestyle changes. This requires an extremely detailed diagnosis and ongoing involvement in the process of change within the patient and his or her environment.

". . . chronic diseases both social and medical are really symptoms of a much more vast underlying problem. They are the final culmination of years of inadequate nutrition, a toxic environment, sedentary lifestyles, familial and social disruptions, and dependence on artificial agents (from cigarettes to cocaine) for happiness."

This approach can also involve much more interest in preventive medicine. In ancient Greece, Hippocrates and his school combined "the pursuit of well-being (symbolized by Hygeia, the goddess of health) and the cure of disease (symbolized by Asclepius, the god of healing)." The authors much prefer this orientation to the present medical concentration on illness and crisis management, for we Americans are, they say, on a dangerous track:

The chronic diseases both social and medical are really symptoms of a much more vast underlying problem. They are the final culmination of years of inadequate nutrition, a toxic environment, sedentary lifestyles, familial and social disruptions, and dependence on artificial agents (from cigarettes to cocaine) for happiness. Every cell in our bodies from the brain to the immune system is affected by these abuses. The effects are particularly devastating in developing children both in and out of the womb. The massive and irreversible loss of human potential in the children of this world is the most disturbing aspect of this planetary destruction. With each underweight, malnourished, poorly educated child born to a malnourished, poorly educated, drug- or alcohol-addicted mother, another bit of the future is lost.

Recommendations

Globally, action on maternal and child nutrition is urgently needed, though we must keep in mind that malnourished mothers and children will not have the mental acuity to learn about ways to improve their condition and that children of the poor in the United States are just as badly off as children in the Third World. The authors recommend "a public/private joint venture to demonstrate in the United States and in one Third World nation, and then market worldwide, a complete nutrient supplement for daily use in indigenous foodstuffs." Poor children, weaned onto cheap starches, have a major protein deficit, resulting in immune deficiencies and less stamina, as well as less mental and physical development. The supplement would have to be easily mixed into familiar foods that the different peoples like. It is hoped that with better nutrition and health, infant mortality would drop, and the people could then consider family planning and a more productive lifestyle.

Locally, or personally, the authors recommendations have a familiar ring: use whole foods (including whole grains), with moderate preparation; include fiber; avoid refined sugar, as opposed to such natural sugars as those in fruit and milk; include protein in every meal, including dairy products for their calcium; eat natural fats, found in fish, olives, nuts, butter, milk, cheese, cold-processed oils, wheat germ, and meat; exercise; eat smaller meals oftener; and "take a comprehensive multinutrient supplement (with food) every day."*

Beware of what they call "tunnel-vision science," for what its popularizers advocate today, they often have to reverse tomorrow, as was the case with polyunsaturated oils. Such sources should be followed with "a little balance and common sense." Above all, "what Americans need most of all is an instinctive preference for whole foods and a healthy sense of suspicion about processed foods."

____________________________

*Though such recommendations would be less helpful to those with food allergies, who may be on rotation diets, they are certainly good advice to many people.

Joseph D. Beasley, MD, is director of the Department of Medicine and Nutrition at the Brunswick Hospital Center, Amityville, New York; Bard Fellow in Medicine and Science, and director of the Institute of Health Policy and Practice of the Bard College Center. Trained in both clinical and preventive medicine, as well as public health and tropical medicine, Dr. Beasley has been a consultant to the World Bank, the Agency for International Development, and the World Health Organization. His advisory work with these and United States government organizations reflects his interest in maternal and child health and in family planning programs.

Jerry Swift, with masters degree in philosophy and theology, and experience in teaching civil rights, has since 1981 worked on health and environmental issues at the Institute of Health Policy and Practice.

Article from NOHA NEWS, Vol. XV, No. 2, Spring 1990, pages 1-4.