CURRENT SOUNDS FROM SILENT SPRING

by

Marjorie Fisher and Lynn Lawson

The contamination of our world is not alone a matter of mass spraying. Indeed, for most of us this is of less importance than the innumerable small-scale exposures to which we are subjected day by day, year after year. Like the constant dripping of water that in turn wears away the hardest stone, this birth-to-death contact with dangerous chemicals may in the end prove disastrous . . . . Lulled by the soft sell and hidden persuader, the average citizen is seldom aware of the deadly materials with which he is surrounding himself; indeed, he may not realize he is using them at all.

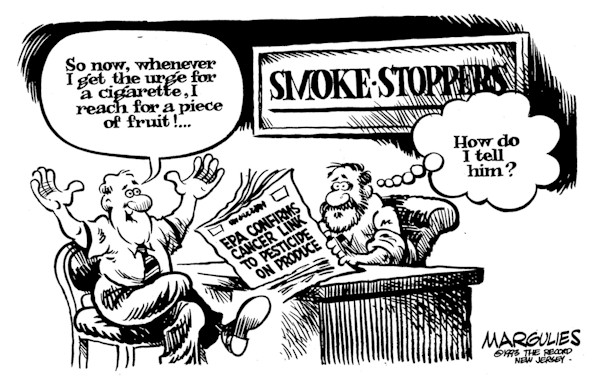

Mr. Jimmy Margulies has granted NOHA permission to make unlimited use of his editorial cartoon on pesticides on fruit.

The year 1987 was the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, from which these words were taken.1 By 1962, Carson, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist and author of The Sea Around Us, had become acutely aware of the contamination of the world by synthetic pesticides and other products of the petrochemical era. At the same time, Theron G. Randolph, MD, of NOHA’s Professional Advisory Board, was discovering that tiny amounts of these ubiquitous chemicals can result in chronic illnesses in susceptible individuals. His book Human Ecology and Susceptibility to the Chemical Environment, based on his previous articles and clinical observations, was published in 1962, a few months before Silent Spring, and is indeed its medical counterpart.2

"With the dawn of the petrochemical era in the late 1940s, annual US production of synthetic organic chemicals was about one billion pounds . . . . By the 1980s [it was] over 400 billion pounds. The overwhelming majority of these industrial chemicals has never been adequately, if at all, tested for long-term toxic, carcinogenic, . . . effects . . ."

What has happened in the quarter century since the publication of Silent Spring? In 1960 the United States produced 638 million pounds of synthetic pesticides3; in 1985, 1.4 billion pounds – a 219 percent increase, representing, according to Samuel S. Epstein, MD, a "runaway chemical technology"4:

With the dawn of the petrochemical era in the late 1940s, annual US production of synthetic organic chemicals was about one billion pounds . . . . By the 1980s [it was] over 400 billion pounds. The overwhelming majority of these industrial chemicals has never been adequately, if at all, tested for long-term toxic, carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic effects . . . .5

Hazardous waste dumps are at present a horrendous problem. In the United States, we now produce in excess of one ton of hazardous wastes per person per year.6 Cancer rates have been increasing:

In 1962, the age-adjusted cancer mortality rate was 170 per 100,000. In 1982, it was 185 per 100,000 . . . . Much cancer today reflects events and exposures in the 1950s and 60s. Production, use, and disposal of synthetic, organic, and other industrial carcinogens were then miniscule compared with current levels, which will determine future cancer rates for younger populations currently exposed. There is every reason to anticipate that the high current cancer rates will be dwarfed in coming decades.7

"According to the Ontario (Canada) Cancer Institute, 60 to 70 percent of all cancers are related to foods." -- Dr. Stuart B. Hill speaking to NOHA December 2, 1987

Faced with such evidence, what action should we take?

In our personal lives, we can follow the excellent advice given by Thomas Stone, MD, in his article "Protecting Your Immune System," in the fall issue of NOHA NEWS. We can try to find water relatively unpolluted by hazardous waste runoff. We can use our important marketplace influence by demanding "organic" food, which NOHA defines as that produced by farmers who have refrained from spraying pesticides on their crops and land and animals, so the food is chemically less contaminated than that supplied by the giant food growers, who use "$6.5-billion worth of farm chemicals a year."8 When pesticide residues are minimized, the food is less likely to overload our bodies' detoxification systems, thus opening the way to serious diseases. By demanding such food, we not only help ourselves, we join other like-minded people in exerting a powerful marketplace influence over the entire food industry.

We can [demand] "organic" food, which NOHA defines as that produced by farmers who have refrained from spraying pesticides on their crops and land and animals, so the food is chemically less contaminated than that supplied by the giant food growers. . . . By demanding such food, we not only help ourselves, we join other like-minded people in exerting a powerful marketplace influence over the entire food industry.

As citizens, we can lobby our legislators for a stronger FIFRA (Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act). FIFRA, set up in 1947 "more as a licensing law than an environmental protection law,"9 has several crucial weaknesses:

|

|

The chemical companies, the agribusiness giants, and the Grocery Manufacturers of America (GMA) are eager to keep the EPA weak. They have a numerous and wealthy lobby. However, as voters, we can insist on effective environmental protection.

The cost to society of using toxic chemicals is very high. Many plastics are designed to be long-lasting. They remain indefinitely in our dumps or, if burned, result in toxic fumes and residues. Pesticides seep into groundwater, which is extremely costly and sometimes virtually impossible to clean up. These costs of pesticides are not borne by the chemical companies, agribusiness, and the grocery manufacturers, they are borne by us.

We can demand the "right to know" about toxic chemicals used in our communities. Dr. Epstein speaks of right-to-know legislation as the "cutting edge" of the fight against toxic chemicals. He says that ordinary people can easily learn the facts then take effective political action. The cost to society of using toxic chemicals is very high. Many plastics are designed to be long-lasting. They remain indefinitely in our dumps or, if burned, result in toxic fumes and residues. Pesticides seep into groundwater, which is extremely costly and sometimes virtually impossible to clean up. These costs of pesticides are not borne by the chemical companies, agribusiness, and the grocery manufacturers, they are borne by us. The fairest way to address this problem is to tax the manufacture and use of these chemicals, insisting on a careful inventory showing any amounts escaping into the air or into waste-water. Thus, wonderful human inventiveness would immediately focus on safe alternatives.

We can pursue safe water, air, and food; use materials that are biodegradable or that can be recycled; and act with others to stem the tide of toxic chemicals that Rachel Carson and Dr. Randolph foresaw so vividly. In Dr. Epstein’s words, "Think globally, act locally!"13

_________________________

1Carson, Rachel, Silent Spring, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, pp. 173-74, 1962.

2In 1962, the two authors did not know each other. However, in April, 1963, a few months before her death, Carson entertained Dr. and Mrs. Randolph and their English guest, Dr. Richard Mackarness, who was then learning about the medical problems from synthetic chemicals in our food, household products, and the outdoor environment. Dr. Mackarness has since applied his knowledge in his clinical practice and in his books, including Eating Dangerously and Chemical Victims.

3Carson, op. cit. P.17.

4Epstein, Samuel S. and Shirley Briggs, "If Rachel Carson Were Writing Today: Silent Spring in Retrospect," Environmental Law Reporter, 17, p. 10180, June 1987. Dr. Epstein, professor of occupational and environmental medicine at the University of Illinois Medical Center in Chicago and president of the Rachel Carson Council, who has spoken for NOHA on "The Politics of Cancer" and on "Hazardous Waste – Source and Solution," both spoke and wrote in commemoration of the anniversary.

5Ibid.

6Ibid., p. 10181.

7Ibid., p. 10182.

8Kaplan, Sheila, "The Food Chain Gang," Common Cause Magazine, September/October 1987, p. 12.

9Ibid.

10Ibid.

11Ibid., pp. 12-13

12Ibid., p. 13.

13Epstein, Samuel S., "Loosing the War Against Cancer: Who’s to Blame and What to Do about It," A Position Paper on the Politics of Cancer, 1987, p. 23.

Article from NOHA NEWS, Vol. XIII, No. 1, Winter 1988, pages 3-4.