The Addiction Pyramid

by

Theron G. Randolph, MD

Theron G. Randolph received his medical degree from the University of Michigan Medical School and is board certified in internal medicine and in allergy and immunology. Author and co-author of numerous medical articles and books, he is considered the father of clinical ecology; is a founder and past president of the Society for Clinical Ecology, now the American Academy of Environmental Medicine; and is president of the Human Ecology Research Foundation.

Nature has a curious way of "protecting" people from cumulative exposures to given foods and/or drugs to which they are highly susceptible. This "protection" essentially erases immediate adverse effects of such reactions, and as long as people resort to their favorite addictant(s) frequently and/or regularly, they simply remain relatively stimulated and symptom-free.

This "protection," which might be referred to as nature’s subtle enigma, went undescribed for centuries. For instance, physicians in ancient Greece knew about allergies to such occasionally eaten foods as cashews and shrimp; but allergy to eggs, the first commonly eaten food to be associated with unrecognized chronic addictive symptoms, was not described until early in the present century. Although wheat, yeast, soy, and other frequently eaten foods had been described as largely unsuspected causes of chronic reactions before 1930, corn – the leading cause of food allergy – was not recognized as such until 1944. Coconut was not recognized as a common, previously undetected cause of reactions until 1989.

Masking commonly occurs when a food to which one is highly susceptible is eaten once in three days or more frequently.

Nature’s way of hiding reactions to commonly eaten foods was first described in the 1930s and 1940s by Herbert Rinkel, MD, as "masking," but this valuable knowledge was not widely disseminated until our book, Food Allergy, was published in 1951. Masking commonly occurs when a food to which one is highly susceptible is eaten once in three days or more frequently. I began referring to masking as "food addiction" in the early 1950s, as this term was far better understood by new patients than "allergy," when referring to a relative absence of symptoms after eating a given food.

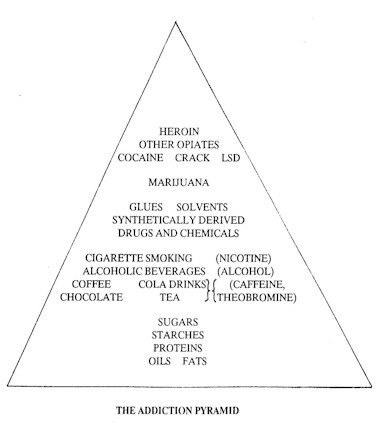

Stages in the development of addictive responses to foods and drugs are best depicted by the addiction pyramid (see illustration). As people gradually become increasingly susceptible and cumulatively exposed to commonly consumed foods, food-drug combinations, and drugs, to which they are reacting unknowingly, they tend to ascend the addiction pyramid.

Starches and sugars are close to the base of the addiction pyramid, from which the susceptible persons tend to ascend successively through such food-drug combinations as chocolate, cola drinks, coffee, and/or tea – all of which are usually consumed with added sugars. Corn is thus especially important, as many sugars are made from corn, with corn being the leading cause of chronic food addiction in this century. As the food-addicted seek to find a more rapidly occurring and more effective stimulatory effect, this subtle addiction process tends to spread through alcoholic beverages and cigarette smoking. Again corn is important, for it is the most common material from which alcoholic beverages are manufactured. And all cigarettes manufactured in the United States since World War I have contained added sugars, commonly corn sugar.

Although this climb up the addiction pyramid may not progress beyond a given level, some developing addicts also come to depend on glues, solvents, and synthetically derived drugs – either self-prescribed or provided by physicians. Coming in contact with other drug users and seeking still more potent stimulants for the relief of their hangover-type reactions, those involved with lesser addictants often experiment with marijuana. This, in turn, may lead them to try LSD, cocaine, crack, and heroin or other opiates, there being little appreciation, especially among the young, of the potential irreversible hazards of such moves.

Corn is thus especially important, as many sugars are made from corn, with corn being the leading cause of chronic food addiction in this century. As the food-addicted seek to find a more rapidly occurring and more effective stimulatory effect, this subtle addiction process tends to spread through alcoholic beverages and cigarette smoking.

Where similar addictive responses might manifest initially as hyperactivity in children or restless legs in adults and might culminate in obesity or alcoholism, true drug addiction is a much more demanding taskmaster, one which commonly defies voluntary control.

Fortunately, the trip up the addiction pyramid is not necessarily a one-way route, although it may be unless one has guidance in descending. And the more advanced the addiction involved, the greater the possibility of fatal accidents. In coming off addictions, it is mandatory that all specifically addicted responses be recognized and that all food-drug combinations containing theobromine, caffeine, alcohol, and/or nicotine, as well as synthetic and natural drugs possessing addictive potentialities or actualities, be avoided simultaneously. Despite the precautions or because of them, the trip down the addiction pyramid is a rough one; relapse at any time must always be considered a possibility.

This version of The Addiction Pyramid and the accompanying article were prepared by Dr. Randolph for this issue of NOHA NEWS and also for the Spring 1990 issue of The Human Ecologist, the magazine of the Human Ecology Action League (HEAL).

Article from NOHA NEWS, Vol. XV, No. 1, Winter 1990, pages 1, 3-4.