LIVING WITH CANCER: A PILOT STUDY OF LONG-TERM SURVIVORS

by Keith I. Block, MD, medical director of the Cancer Treatment Program at Edgewater Medical Center in Chicago; director of Nutritional and Psychosocial Oncology at Midwest Regional Medical Center in Zion, Illinois, with private practice in internal medicine in Evanston, Illinois,

Charlotte Gyllenhaal, PhD, Program for Collaborative Research in the Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago,

and Penny B. Block, MA, Department of Social Services Administration, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

The multi-dimensional need for adjuvant nutrition in cancer care is slowly commanding the attention of oncologists. Cancer physicians have certainly for decades recognized the basic nutritional implications of malignancy: the prevalence of malnutrition and cachexia in late-stage patients, the need for enteral and parenteral dietary supplements at certain critical junctures. But the breadth and variety of the contributions of a truly appropriate diet for cancer patients in all stages of their disease has only recently begun to be appreciated.

The roots of this later realization lie in significant advances in the dietary epidemiology of cancer that occurred in the 1980’s and early 1990’s. Many of these studies are critically important for progress in cancer prevention. One such study is by T. Colin Campbell and his colleagues in China, who surveyed the incidence of cancer and other diseases in a national population that consumes a diet based much more solidly on grains, vegetables and plant proteins than the American diet.

Cancer physicians have certainly for decades recognized the basic nutritional implications of malignancy: the prevalence of malnutrition and cachexia in late-stage patients, the need for enteral and parenteral dietary supplements at certain critical junctures.

But the significance of these studies does not stop with disease prevention. Traditional plant-based diets that inhibit the processes of cancer initiation and progression are, we feel, critical to issues of cancer survival once disease has been established. While this topic has been discussed at some length previously (Block, 1993), it is worth reviewing just a few of the studies that bear on it here.

Breast cancer is one of the diseases in which diet may have a major role. Holm et al. (1993) showed that among Swedish breast cancer patients, those who experienced recurrence of disease two to four years following surgery had significantly higher fat intakes (40.4% of diet) than those who did not experience disease recurrence during this time (36.0% of diet). Saturated fat intake was the variable most closely associated with recurrence. While the fat levels in this study are considerably higher than would be clinically advisable, they do demonstrate the powerful effect that dietary adjustments can potentially make. Several studies comparing breast cancer patients in Japan with those in Western countries put the results of Holm’s study in a larger dietary context and a longer time frame: investigators found that Japanese women had higher five- or ten-year survival rates than women in the United States or the United Kingdom (Wynder et al., 1963; Morrison et al., 1973; Nemoto et al., 1977; Sakamoto et al., 1979).

The hormonal implications of dietary fat in relation to breast cancer have been explored extensively, e.g. by Rose and Connolly (1990). Also telling is work that points to the negative correlation of body weight with breast cancer survival (Donegan, 1978; Rose and Connolly, 1990). These studies point to diets low in fat and high in complex carbohydrates as potential contributors to breast cancer survival, an idea now being explored experimentally in the trials of the Women’s Health Initiative.

Prostate cancer is another malignancy that may be related to diet. Giovannucci et al. (1993) report that men with advanced prostate cancer, but not men with early stage cancers, had higher consumption of saturated fat and alpha-linolenic acid than did controls. Foods especially correlated with advanced cancers included bacon, creamy salad dressings, butter, and red meat. Again, cross-cultural studies provide a larger framework for Giovannucci’s studies. Much of the cross-cultural work concerns prostate cancer observed at autopsy: studies in several countries have analyzed autopsy materials for subclinical prostate cancers, which can be classified as proliferative or infiltrative types, versus non-proliferative or non-infiltrative types. The proliferative/infiltrative types are more closely related to clinically significant prostate cancer than the non-proliferative/non-infiltrative types. Results of studies comparing rates of the different histologic types consistently found that men from Japan and other countries eating low-fat plant-based diets have lower rates of proliferative/infiltrative types than those from countries eating diets high in fat and animal foods. In comparison with standard survival figures, prostate cancer patients employing the macrobiotic diet had increased survival times.

In sum, the scientific literature shows that a low-fat, plant-based diet has many potential contributions to make in the care of cancer patients. There are, however, an enormous number of questions to be explored on this issue.

Cancer patients frequently contend with immune suppression, induced either by malignancy or by aggressive conventional treatments. Dietary fat, both the levels and the types, may affect immune cells. Barone et al. (1989), for instance, found that men who consumed less than 25% of their calories from fat had higher natural killer cell activity than those consuming more fat. These results were not affected by reduced total caloric intake, weight, exercise, or other variables related to fat. Omega-6 fatty acids appear to be more immunosuppressive than omega-3 fatty acids in clinical situations because of their production of immunosuppressive prostaglandins such as prostaglandin E2 (Lowell et al., 1990; Hamawy et al., 1985; Seidner et al., 1989). High fat levels, especially high omega-6 levels, also appear to promote metastasis in several animal tumor models (Erickson and Hubbard, 1990; Rose et al., 1991).

Other features of plant-based diets may also affect survival. Scholar et al. (1989) found that consumption of collards and cabbage inhibited pulmonary metastases of a mouse mammary tumor line. Women with lung cancer in Hawaii who ate greater amounts of vegetables experienced lower rates of death than those who ate fewer vegetables, although this effect was diminished among obese patients (Goodman et al., 1992). Genistein, a soybean isoflavone, is a phytoestrogen capable of binding to estrogen receptors and has recently been found to inhibit the growth of blood vessels in tumors: both activities may be relevant in cancer survival.

Both the type and the amount of protein in the diet may be of relevance to cancer patients. Toniolo et al. (1989) observed that the consumption of animal protein increased risks of breast cancer in Italian women, even after statistically removing the effects of fat from the animal protein sources. Protein sources may also affect reactions to treatment. Sitren et al. (1993) gave methotrexate, a cancer chemotherapy agent, to mice on a soy-protein diet and compared them with those on a casein diet. Mice fed soy proteins had lower mortality than the casein groups (Sitren et al., 1993). Amounts of protein in the diet may also be affecting tumor growth. In rats fed diets varying in protein levels and exposed to the carcinogen DMBA, the group with the highest protein levels (31%) had the highest incidence of mammary tumors, and the most advanced tumors (Hawrylewicz et al., 1982). Dietary protein increases the enzymatic activation of the liver carcinogen aflatoxin B1 when ingested by rats (Preston et al., 1976; Appleton and Campbell, 1982).

In sum, the scientific literature shows that a low-fat, plant-based diet has many potential contributions to make in the care of cancer patients. There are, however, an enormous number of questions to be explored on this issue. How low in fat should the diet be? What fats should be emphasized and de-emphasized? At what stage of disease should the diet be implemented? What supplements should be used? Do supplements help or hinder chemotherapy? Can patients with catastrophic disease really be expected to change their diets effectively? How could dietary change fit into the complex family dynamics that sometimes develop around a chronically or acutely ill person?

We propose to explore three of these issues. First we will briefly discuss how low fat levels should be, and when it is appropriate to recommend diets with differing fat levels. Second, we will present a model program that blends dietary change with conventional cancer therapy, psychosocial support, exercise and body care, and systematic supplementation. Third, we shall discuss results of a pilot study of long-term cancer patients, who have participated in this program, to assess how well they were able to adapt and adhere to the program long term, what challenges they found in making diet and lifestyle transition, and how they addressed those challenges.

Dietary Fats: Tailoring to Individual Needs

We will discuss three different dietary compositions that have potential application in cancer. One is the macrobiotic diet, where patients consume diets with10-13% fat content. In the Paleolithic diet 30% fat is recommended, comprising a high percentage of omega-3 fatty acids and gamma linolenic acid plus protein consumption of approximately 30% of calories. The dietary pattern we recommend for cancer patients has 15-18% fat content. All the different low-fat diets are suggested to have relevance to cancer patients. But which one is the right pattern? Or, perhaps we should ask, which one is right for a particular patient at a particular stage of disease?

Ultimately, we feel, there is no justification for saying that any one of the three dietary patterns is the one right diet for all cancer patients at all times. Rather, the diet must be adapted to the individual patient and his or her particular condition and direction of treatment at a given time.

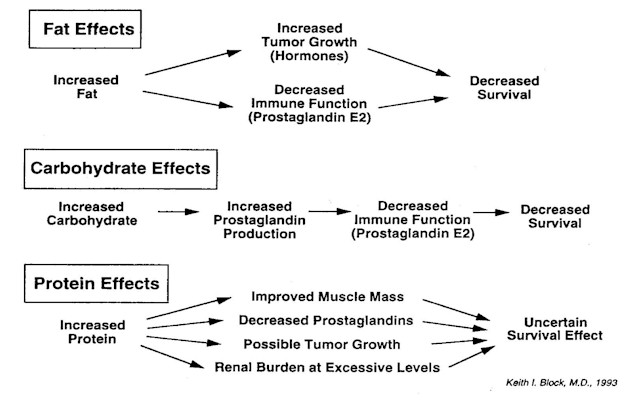

There is, in fact, a basic metabolic tension underlying these three dietary patterns, a tension that concerns the effects of fats, carbohydrates and proteins on tumor growth, especially as mediated through the arachidonic acid cascade and through hormonal effects. This tension is illustrated in Figure 1. Proportions of the three macronutrients, fat, protein, and carbohydrate, can be varied to determine diet composition. If dietary fat is increased, tumor growth may be stimulated by increased levels of reproductive hormones derived from saturated fats, or by prostaglandins derived from omega-6 fatty acids. If carbohydrates are increased, particularly simple sugars, the resulting higher blood levels of insulin may stimulate the production of inflammatory and tumor-promoting prostaglandins. Protein increases beyond the normally calculated protein requirements may burden the kidneys and may promote tumor growth, although the latter possibility is not yet as well established experimentally as the effects of prostaglandins on tumor growth.

Figure 1

Effects of increasing dietary fat or carbohydrate can be modulated, of course, by further specifying dietary composition. The arachidonic acid cascade can be shifted towards less harmful prostaglandins by the use of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and gamma linolenic acid. When needed, the use of monounsaturated oils (like olive oil) and medium-chain triglycerides1 can increase fat content (and thus caloric intake) without increasing prostaglandins. Elevated blood levels of insulin resulting from release of glucose into the bloodstream in high-carbohydrate diets can be diminished by feeding complex carbohydrates and high-fiber diets. And the determination of which macronutrients and which foods and supplements should be recommended must also be viewed in the context of a patient’s appetite and capacity to take in and digest food.

Ultimately, we feel, there is no justification for saying that any one of the three dietary patterns is the one right diet for all cancer patients at all times. Rather, the diet must be adapted to the individual patient and his or her particular condition and direction of treatment at a given time. Diet can play a critical role for specific patients at specific times. For one group, the well-nourished patients in remission, the 10-13% fat or the 15-20% fat diets would be suitable: the particular fat level selected may depend on individual taste, capacity to make major dietary changes and adhere to them, support, and individual metabolism. For a second group, the mildly malnourished patients or the well-nourished patients with active disease, especially when undergoing conventional treatment, the caloric density of a 10-13% fat diet may be too low, while a 30% fat diet may be too high in fat (even omega-3 fatty acids may adversely affect the immune system when given at high levels, in part because of the tendency of omega-3 fatty acids to peroxidize). For a third group, the moderately to markedly malnourished patients, increasing protein and fat levels may be quite appropriate until the malnutrition is corrected, as long as protein comes from sources low in omega-6 and saturated fatty acids (i.e. cold-water fish, legumes), and as long as the overall fat composition of the diet is shifted away from the production of inflammatory prostaglandins. Finally, for any of these three groups, proper supplementation and adapted exercise<197>even for bedridden patients<197>are important components of a nutritional program.

A Model Program

We have been using a program whose nutritional base is the 15-18% fat diet in clinical practice for well over a decade. The major thrust of the program is improving the overall fitness of cancer patients (and patients with other diseases as well as health maintenance concerns) with a multi-dimensional intervention that addresses biomedical, biophysical, nutritional, and psychosocial aspects of disease and health care.

The aims of the program we have developed for patients in cancer therapy are to diminish the stress and side effects of conventional cancer treatments, to lower risks of recurrence, to enhance survival where possible, and to empower patients to assume control of their lifestyle and life by initiating a comprehensive health regimen. A constant theme throughout the program is a compassionate approach to care that recognizes the whole person, and not just his or her disease. Our counseling for lifestyle change is done with full recognition of the intense cultural, social, familial, and emotional meanings that food has for most people. We specifically attempt to defuse unproductive theories of self-blame that plague many cancer patients.

The exercise component of the program is critical in maintaining or building muscle mass. Instituting low fat diets without physical conditioning can, in some cancer patients, lead to rapid degradation of body composition.

At the base and foundation of the program is what we call medical gradualism, which is an approach to health care premised on the idea that mild conditions should be treated with non-invasive, non-aggressive strategies, while increasingly severe conditions are approached with increasing invasiveness and aggressiveness when deemed of clinical benefit and when this course is actively chosen by the patient. It is a resolution not to "use a cannon when a fly swatter will suffice"; however, at the same time, to encourage the use of more aggressive therapies when they are necessary and when the patient is informed and in agreement that it is worth proceeding.

Full diagnostic profiling is completed with patients going through the program. Both medical diagnoses and biomechanical-biophysical conditions are assessed, by measuring muscle mass and body composition in addition to the medical history and indicated laboratory tests. The options for conventional treatment rest on the medical findings; body composition and muscle mass data are used in developing a program of nutrition, exercise, and body work adapted to the state of the patient.

Stress profiling and emotional-social assessment are also important aspects of the program. Stress management techniques used include meditation, journal-keeping, progressive relaxation, visualization, and biofeedback. We also refer patients to life-affirming support groups meeting in their areas when possible, and do encourage their participation in such groups.

Exercise

The exercise component of the program is critical in maintaining or building muscle mass. Instituting low fat diets without physical conditioning can, in some cancer patients, lead to rapid degradation of body composition. Particularly worrisome is muscle loss. With the anabolic stress created by exercise, however, patients can gain or maintain muscle tissue while losing fat tissue. This is in marked contrast to the catabolic stress of cachexia, in which patients lose both muscle and fat tissue, even while perhaps eating diets with high percentages of fat and protein. By using an electrical impedance system we have been quite successful in making assessments of body composition to distinguish healthy loss of fat tissue due to a combination of diet and exercise from weight loss due to illness, treatments, inadequate food intake, or inadequate adherence to the diet and exercise program. Additional aspects of the biomechanical phase of the program are acupressure, massage, body work, acupuncture, and microelectrical stimulation therapy. The latter is particularly aimed at pain relief.

To be effective with dietary interventions, the individuals’ personal leanings are of critical importance if success with adherence is to occur. The primary fats used are canola and olive oil, along with limited intake of seeds and nuts; long chain omega-3 fatty acids in both cold-water fish and dietary supplements are also used.

Diet

The dietary component of our program is the feature for which we are best known. While we do individually tailor percentages of macronutrients according to the particular needs of a particular patient, the diet most frequently recommended comprises 15-18% fat, 15-20% protein and 65% carbohydrate. Adjustments in percentages are based not only on the individual clinical needs but also the social needs and personal motivations of the patient. To be effective with dietary interventions, the individuals’ personal leanings are of critical importance if success with adherence is to occur. The primary fats used are canola and olive oil, along with limited intake of seeds and nuts; long chain omega-3 fatty acids in both cold-water fish and dietary supplements are also used. Gamma linolenic acid may be given supplementally. Protein is chiefly vegetarian, with an option for some fish as desired by those less inclined toward a vegetarian diet and for those patients needing more protein-rich foods. Legume proteins, especially soy foods, are highly recommended. Carbohydrate sources are whole grains, vegetables, and fruits. Sea vegetables are recommended, as is consumption of miso and other soups. Complex carbohydrates are recommended, rather than simple sugars. Since complex carbohydrates usually come from fiber-rich foods, this eating pattern minimizes blood sugar swings.

. . . we have been quite successful in making assessments of body composition to distinguish healthy loss of fat tissue due to a combination of diet and exercise from weight loss due to illness, treatments, inadequate food intake, or inadequate adherence to the diet and exercise program.

The dietary regimen was developed by Keith Block, M.D., based on a refinement of the macrobiotic diet following years of clinical application and investigation. The macrobiotic diet is, in principle, nothing more than the traditional Japanese diet, recast somewhat for Western tastes and sensibilities. In the course of working with many cancer patients who adopted the macrobiotic diet in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, however, it became apparent that a more systematic approach than that offered by the macrobiotic community was necessary for catastrophic diseases and treatments. Thus, with the collaboration of university dietitians, Block transformed the diet into a series of exchange lists, allowing individualized recommendations for quantities of grains, protein foods, vegetables, fruits, and fats. The exchanges ensure both adequate caloric intake and proper balance of macronutrients at any needed caloric level. Other modifications were made in order to be more clinically and scientifically sound, to facilitate adherence, and to avoid the limitations found in cooking according to a single cultural slant.

In addition to the exchange lists, we have also constructed a list of foods to be reduced or totally avoided. On this list are red meats, poultry, polished grains, refined flour and sugar, artificial sweeteners, carbonated beverages, eggs (occasional free-range eggs are acceptable), and dairy products. We counsel against the use of alcohol except for occasional use of beer or small amounts of wine used in cooking (e.g. mirin, a Japanese sweet wine). Stimulants including caffeine, illicit drugs, and tobacco are also to be avoided. Supplementing the avoid list is a list of foods that can be used as transitional items when starting the diet or on occasions when recommended foods cannot be obtained. This list includes organic free-range chicken, white rice, refined-flour pasta, skim milk yogurt, and other skim milk products.

Block transformed the diet into a series of exchange lists, allowing individualized recommendations for quantities of grains, protein foods, vegetables, fruits, and fats. The exchanges ensure both adequate caloric intake and proper balance of macronutrients at any needed caloric level.

We also have a third class of foods that are regarded as questionable in certain circumstances. Especially relevant to cancer patients with active disease are vegetables in the plant family Solanaceae (nightshades), particularly tomatoes which are high in sugar and excessively acidic, as well as eggplant and peppers. Citrus fruits and juices are often poorly tolerated by many cancer patients whose guts are compromised by conventional treatment. A number of allergenic foods are also on the Reduce/Avoid list, since gut wall injury can allow food particles to enter the circulation triggering allergic syndromes. Also, not inconsequentially, gut wall permeability syndrome and its resultant increase in circulating immune complexes can diminish the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic agents. We feel, therefore, that it is important to avoid any foods that may further compromise the intestine.

While the dietary regimen is the principal basis of nutrition in the program, we also actively employ nutritional and botanical supplementation. Enteral and, in some patients undergoing chemotherapy, parenteral nutritional supplements are used to boost caloric levels when oral intake is inadequate. Other agents that we call, "Innovative Low-Invasive Therapeutic Tools," are aimed not only at ensuring optimal nutrient intake but also at counteracting specific problems resulting from cancer therapies. They include long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, gamma linolenic acid, shiitake mushroom, garlic, echinacia, astragalus, eleutherococcus, carotenoids, antioxidant vitamins, and acidophilus. A full-spectrum multi-vitamin supplement is also used.

It is important, finally, to restate that we also utilize the entire regimen for many clinical conditions other than cancer along with an overall prevention/optimal fitness system for those interested in better health and peak performance.

The Long-Term Survivors Adherence Study

The program we have described above emphasizes lifestyle change and improvement of nutritional, physical, and mental fitness as part of a comprehensive plan for cancer treatment as well as prevention. In fact, the program seeks what are for many people very substantial lifestyle changes, which must be maintained for long periods. A natural question is whether patients are able to make and sustain the degree of change sought in the program.

We recently undertook a study of adherence to lifestyle recommendations. We also wanted to know how well we were assisting patients in translating the scientific system we work under into actual behavior change. Finally, we wanted to know if we could learn anything from our patients that would enhance our ability to care for others.

. . . the program seeks what are for many people very substantial lifestyle changes, which must be maintained for long periods. A natural question is whether patients are able to make and sustain the degree of change sought in the program.

This survey details the experience of a self-selected group of patients who sought out the program aware that it entailed changes in diet and other aspects of lifestyle. They were motivated to seek a more comprehensive as well as more "natural" means of approaching cancer treatment and were willing to commit personal resources of time and energy towards that end. Their willingness to take responsibility for their own health care may very well be related to their long-term survival.

The questionnaire used as a measurement tool in this study was constructed in collaboration with staff at the University of Illinois at Chicago. We constructed our own questionnaire rather than using standard instruments since none of the available instruments targeted the specific aspects of lifestyle we wished to address. The long-term survivors included in the study were selected by examination of medical charts.

Study Population

Ten patients were interviewed. Their ages at diagnosis ranged from 33 to 74. A majority of the patients were over age 55 when they began the program. When studied their survival times ranged from 15 years, 2 months to 3 years, 4 months since diagnosis. All of these patients are still alive and their average survival time is now 7 years, 6 months since diagnosis, with all of these patients living active lives. A variety of different cancer diagnoses are represented in the group. At the time of diagnosis, two patients in the group were living alone and eight with spouse and/or parents. Three had children living at home.

Before entering the program, five patients had undergone surgery, three radiation, and three chemotherapy. Two patients had had other treatments. Five had sought alternative treatments before coming to the program.

Dietary Change

The interviews revealed that seven patients were the only members of their households who followed dietary recommendations made in the program. In only three cases did other household members follow the dietary recommendations.

Patients are given recommendations for dietary change on the first visit to the program. We questioned patients in the study about the changes they made in the first week following the initial visit. One patient spent the first week considering whether to adopt the recommended changes. Three reported making preparations to change. Five had already modified their diets through contact with the macrobiotic diet and began making recommended refinements in their already-altered diets. One patient made a major change from the standard American diet in the first week.

The group reported that at the time of the study they adhered strongly to the program: nine reported that they almost always adhered to the dietary recommendations; only one went off the program on a monthly basis; and none deviated from the program on a weekly basis or more frequently than a weekly basis.

Although the group reported high levels of adherence to the diet, the transition was not without challenges. Some of the challenges the group faced in making the change were dealing with attachments to non-recommended foods or dislikes of recommended foods (reported by 8), mastering new cooking techniques and having time to cook (7), feelings of deprivation and problems in dealing with social life (6) and having to cook different foods for different family members (5). Fewer reported problems with expense2 (3) or lack of support from household members (3), extended family (4), or friends (4).

These challenges, nevertheless, apparently did not preclude the group from making new adaptations. In the area of social life, for instance, patients found ways to adapt restaurant eating to their new dietary habits. Many patients ate most meals at home: nine of the patients ate home-cooked dinners five or more times per week while only one ate as few as three or four home-cooked dinners per week. The patients chose predominantly ethnic restaurants (Chinese, Greek, Indian, and Italian) and vegetarian restaurants when they decided on where to eat; none chose fast food restaurants. Many reported patronizing fine dining or gourmet restaurants. When foods most highly recommended on the dietary program were unavailable at restaurants, patients chose other foods including white rice, white potatoes, and chicken. Red meat, fried foods, and sugary desserts were each eaten by only one patient, though this was done quite infrequently. One patient reported simply not eating if no suitable foods were available, and three reported that they did not go to a restaurant unless it served suitable foods.

Some of the challenges the group faced in making the change were dealing with attachments to non-recommended foods or dislikes of recommended foods (reported by 8), mastering new cooking techniques and having time to cook (7), feelings of deprivation and problems in dealing with social life (6) and having to cook different foods for different family members (5).

Other social situations involve eating at the homes of friends or family. We queried the group about how they handled this situation. Bringing their own foods was mentioned by seven patients as a response to this situation. Four patients reported educating their hosts about acceptable foods, three reported eating before they went out so that they would not be hungry, three ate selectively from whatever foods were served, two called ahead to determine what would be served, and one simply ate whatever was served.

Many "healthy" convenience foods are now available in natural foods grocery stores. We questioned patients about their use of these foods. Five of the patients reported using these foods more than three times per week; five reported that they used them three times per week or less. The most popular convenience food was dried miso soup, used by five patients. Other foods, such as frozen vegetables, frozen vegetarian meals, soy cheese, vegetarian pizza or vegetarian burgers3 were used by only one or two patients each.

We queried patients about their use of specific foods on the exchange lists and on the Reduce/Avoid list. Nine patients ate miso more than twice a week, and seven ate other soy foods more than twice a week. Seven patients ate fruit more than twice a week. Seven never ate chicken, the others ate it infrequently, at most once a week. Five never ate fish; five ate it once a week or less. No patients reported eating dairy products. Five ate sea vegetables twice a week or more. We also questioned patients about how frequently they ate the nutritional "powerhouse" vegetables (dark leafy greens, cruciferous vegetables, and orange-yellow vegetables). Six patients reported eating vegetables from this group more than once a day, two ate them once a day and two ate them less than once a day.

We noted that for all questions regarding dietary adherence, the less-than-optimal responses were distributed among most of the patients, rather than being entirely from one or two patients, indicating that most patients made a few deviations, rather than that a few patients made most of the deviations.

Other Lifestyle Recommendations

Increasing levels of exercise is an important component of the program. We questioned patients about the types and frequency of exercise they engaged in before entering the program, after entering the program, and at the time of the study. The most popular types of exercise among those we listed were walking and biking or using a stationary bike.

Most of the patients reported engaging in more than one type of exercise. The program did not appear to affect much change in the type or variety of exercise performed. Patients did, however, increase the frequency of exercise sessions; before entering the program only one patient exercised daily; after entering the program, four patients exercised daily. At the time of the study, four patients were still exercising regularly.

As with exercise, there was a small change in the types of stress management techniques employed before and after entering the program and at the present. The frequency with which these techniques were practiced, however, increased markedly. The types of stress management techniques employed by five or more patients after entering the program were meditation (6, increase of 4 over pre-program), progressive relaxation (5, increase of 4), prayer (5, increase of 3) and visualization (5, increase of 4).

What is clear from the present study is that a self-selected group of patients can make and adhere to major shifts in diet in the midst of catastrophic illness. It is not necessary for other family members to shift diets at the same time, although most do report receiving verbal support from family members. We believe, however, that family involvement in making dietary changes would logically be of emotional benefit to patients’ wellbeing and adherence.

The use of personal support networks is also encouraged in the program: efforts are made, for instance, to include family members in patient visits and other discussions. Patients were asked whether there were people with whom they were able to discuss their fears, frustrations and concerns. Eight reported having such discussions, six with family members, six with friends, five with their doctor (most mentioning specifically the first author), and two each with clergy members and support group members. None reported having these discussions with counselors or therapists.

Five of the patients reported receiving negative comments about their lifestyle changes. Two patients dealt with these comments by cheerfully ignoring them, one by forgiveness, one by avoiding people who make negative comments, and one by pointing out the good results of the lifestyle changes.

Patients reported improvements in their quality of life following the adoption of the program. Eight reported having better energy levels, three reported better appetite, and two each reported improvement in aches and pains, waking more easily, requiring less sleep and feeling calmer. One regained weight lost due to disease. Two patients felt better immediately after adopting the program, four felt better some time later (four did not specify time in answering this question).

Attitudinal Questions

Perhaps particularly revealing about this group was our finding that nine of the ten patients desired to participate actively with their doctors in making medical decisions; only one patient stated a preference for simply accepting a doctor’s decision. Several patients reported in comments that they felt that their optimistic attitudes contributed to their success in battling their illnesses.

The group was also queried about whether mental states could have an impact on disease. Nine patients felt that thoughts could impact disease; one did not know whether they could.

Patients felt there were multiple causes for their illnesses. Nine patients attributed causation to stress, eight to diet, five each to radiation and genetic background, four to pollution, three to smoking (including secondhand smoke) and one to alcohol use. We also asked patients if there was a possibility that particular stressful events contributed to causing their disease. Four patients cited such events.

Conclusion

What is clear from the present study is that a self-selected group of patients can make and adhere to major shifts in diet in the midst of catastrophic illness. It is not necessary for other family members to shift diets at the same time, although most do report receiving verbal support from family members. We believe, however, that family involvement in making dietary changes would logically be of emotional benefit to patients’ wellbeing and adherence. The long-term-survivor cancer patients we interviewed were optimistic, and felt that thoughts and feelings significantly impacted disease states. They were able to increase their use of exercise and stress management techniques. Although most did not need frequent discussions to address their fears and concerns, when they did need such discussions, they sought out family members and friends rather than professional counselors or therapists. And although all reported challenges in making the dietary transitions, they had developed successful strategies for dealing with the problems. The changes they made in their diets were maintained for long periods. Whether the comprehensive clinical program the patients undertook is responsible for the quantitative changes in the patients’ survival cannot be definitively determined from our study. Nonetheless, qualitative improvement was evident. Further studies will be needed to determine if diet and lifestyle interventions can actually impact cancer survival.

___________________________

1A specially fractionated oil containing fat buiding-blocks of medium molecular length. Medium-chain triglyceride oil can sometimes be found in health food stores; the term "MCT oil" will usually be on the packaging.

2Once the initial outlay is made for basics, the overall costs are significantly less than for a more typical American diet.

3Some of these may contain MSG.

References

Appleton, B.S., and T.C. Campbell, ""Inhibition of aflatoxin-initiated preneoplastic liver

lesions by low dietary protein,"Nutrition and Cancer, 3(4): 200-6, 1982.

Barone, J., J.R. Hebert, and M.M. Reddy, "Dietary fat and natural killer cell activity," American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 50: 861-7, 1989.

Block, K.I., "Dietary impact on quality and quantity of life in cancer patients" in Quillin, P. and Williams, R.M., Adjuvant Nutrition in Cancer Therapy, Cancer Treatment Research Foundation, Arlington Heights, Illinois, pp. 99-127, 1993.

Carver, C.S., C. Pozo-Kaderman, S.D. Harris, V.Noriega, M.F. Scheier, D.S. Robinson, A.S. Ketcham, F.L. Moffat, Jr., and K.C. Clark, "Optimism versus pessimism predicts the quality of women’s adjustment to early stage breast cancer," Cancer, 73: 1213- 20, 1994.

Erickson, K.L., and N.E. Hubbard, "Dietary fat and tumor metastasis,""Nutrition Reviews, 48: 6-14, 1990.

Giovannucci, E., E.B. Rimm, G.A. Colditz, M.J. Stampfer, A.Ascherio, C.C. Chute, and W.C. Willett, "A prospective study of dietary fat and risk of prostate cancer,""Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85: 1571-9, 1993.

Goodman, M.T., L.N. Kolonel, L.R. Wilkens, C.N. Yoshizawa, L.LeMarchand, and J.H. Hankin, "Dietary factors in lung cancer prognosis,""European Journal of Cancer, 28(2/3): 465-501, 1992.

Halstead, M.T., and J.I. Fernsler, "Coping strategies of long-term cancer survivors,""Cancer Nursing, 17: 94-100, 1994.

Hamawy, K.J., L.L. Moldawer, M. Georgieff, A.J. Valicenti, A.K. Babayan, B.R. Bistrian, and G.L. Blackburn, "The effect of lipid emulsions on reticuloendothelial system function in the injured animal,"Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 9: 559-65, 1985.

Hawrylewicz, E.J., H.H. Huang, J.Q. Kissane, and E.A. Drab, "Enhancement of 7-12- dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) mammary tumorigenesis by high dietary protein in rats,"Nutrition Reports International, 26(5): 793-806, 1982.

Holm, L.E., E. Callmer and M.L. Hjalmer, "Dietary habits and prognostic factors in breast cancer,""Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 81: 1218-23, 1989.

Lowell, J.A., H.L. Parnes, and G.L. Blackburn, "Dietary immunomodulation: beneficial effects on oncogenesis and tumor growth,"Critical Care Medicine, 18: S145-8, 1990.

Morrison, A.S., M.M. Black, C.R. Lowe, B. MacMahon, and S. Yuasa, "Some international differences in histology and survival in breast cancer," International Journal of Cancer, 11: 261-7, 1973.

Nemoto, T., T.Tominaga, A. Chamberlain, Z. Iwasa, H. Koyama, M.Hama, I. Bross, and T. Dao, "Differences in breast cancer between Japan and the United States," Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 58(2): 193-7, 1977.

Preston, R.S., J.R. Hayes, and T.C. Campbell, "The effects of protein deficiency on the in vivo binding of aflatoxin B1 to rat liver macromolecules," Life Sciences, 19: 1191-8, 1976.

Rose, D.P., J.M. Connolly, and C.L. Meschter, "The effect of dietary fat on human breast cancer growth and lung metastasis in nude mice,"" Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 83: 1491-5, 1991.

Sakamoto, G., H. Sugano, and W.H. Hartmann, "Comparative clinicopathological study of breast cancer among Japanese and American females," Japanese Journal of Cancer Clinics, 25: 161-70, 1979.

Scholar, E.M., K. Wolterman, D.F. Birt, and E. Bresnick, "The effects of diets enriched in cabbage and collards on murine pulmonary metastasis,"" Nutrition and Cancer, 12: 121-6, 1989.

Seidner, D.L., E.A. Mascioli, N.W. Istfan, K.A. Porter, K. Selleck, G.L. Blackburn, and B.R. Bistrian, "Effects of long-chain triglyceride emulsions on reticuloendothelial system function in humans," Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 13(6): 614-9, 1989.

Sitren, H.S., L.G. Johns, B.S. Solomon, and P.I. Solomon, "Modulation of methotrexate (MTX) toxicity by protein-source in solid diets and in enteral formulas,"" Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 17(1, Supplement), 32S, 1993.

Toniolo, P., E. Riboli, F. Protta, M. Charrel, and A.P.M. Cappa, "Calorie-providing nutrients and risk of breast cancer," Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 81(4): 278- 86, 1989.

Wynder, E.L., T. Kajitani, J. Kuno, J.C. Lucas, A. DePalo, and J. Farrow, "A comparison of survival rates between American and Japanese women patients with breast cancer," Surgery, Gynecology, and Obstetrics, 117: 196-200, 1963.

Article from NOHA NEWS, Vol. XX, No. 1, Winter 1995, pages 6-12.